Children’s Ward Engagement

About This Project

The integration of site-specific art into health facilities is increasingly prevalent world-wide and there is growing research showing many benefits to patients, staff and visitors resulting from integrating arts into healthcare.

This is not a new concept, with Florence Nightingale’s ‘Notes for Nursing’ published in 1859, a pre-cursor to the art initiative in hospitals today. She described the patients’ need for beauty and making the argument that the effect of beauty is not only on the mind, but on the body as well.

Kathy Hathorn and Upali Nanda’s, ‘Guide to Evidence-Based Art’, explores the different levels at which art can improve the quality of healthcare and reports on the evidence making a strong case that art is a critical component of the healthcare environment, which can aid the healing process.

As a child of the nineties as a bouncing yet breakable eight-year-old, I required surgery and a short stay in the old hospital’s Paediatric Ward. Upon reflection, the corridor painted in a star-scape of yellow, purple and glitter on the way to surgery sticks in my mind above the fear I would have felt at the time.

Quite recently, I experienced what it was like to be a parent in the Paediatric Ward when on three separate occasions I faced all the waves of emotion and an eternity of wait times for my daughter, Matilda to come out of the surgery which would realign her clicky hips.

As a result of this personal connection to the hospital, I’m empathetic to patients and their families who are at their most vulnerable. The rationale behind my initial proposal stated how much it would mean to me to be the one responsible for making the pictures and the positivity stick in the minds of people. And for the ward to be a place where those who worked there, looked forward to being there and stressed a little lesser there as a result of their environment.

The objective of the body of work I created within the Paediatric Ward was to transform the space into a healing and hopeful environment, with a little bit of heart. This was difficult to achieve during the redevelopment phase, where all I had for inspiration within the space were air conditioning ducts, construction workers and an elevator lined with graffitied chip board!

Thankfully, I had Matilda who, at the time of the first phase of creation, was a sparkling, talkative two-year-old. I developed the story with her coming on board as an advisor and from the behaviour I started to observe, the story was becoming ingrained into her life, just as much as it was mine. She would share her thoughts on the direction of the story or what she thought of the pictures as she sat on my lap. She’d direct the placement of the malleefowl in the artwork or select the colours of certain objects from the palette. Only once she commented the artwork was “boring”, so I turned the trees red and made the leaves appear to be falling until she said, “good job, Mummy.” Other times she would actually interact with an imaginary Mallie in play.

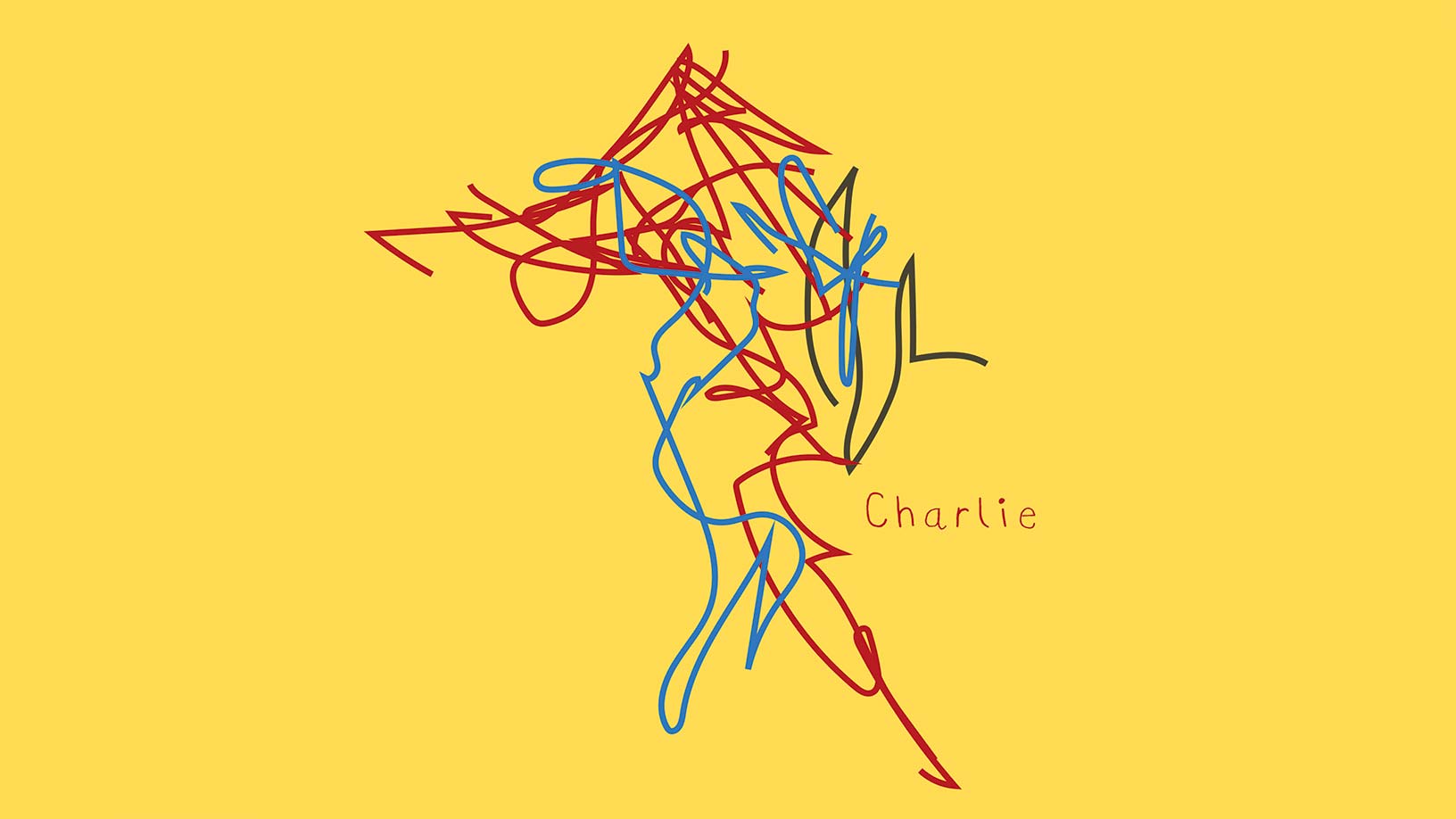

When the staff at the Paediatric Ward approached me to create a second phase, the first thing I asked was, ” can I draw with the children this time?!” And so began an engagement process and the beginning of stories inspired from their environment woven into the already established ones.

Mallie the mallefowl is still shy and wary after being chased by a fox into a capricious new world with Doctor Kangaroo’s and nurse echidnas, but now he has Zara’s fairy house to visit and Charlie’s aeroplane to fly in. While I drew with the patients, I had a chance to tell them the story from beginning to end (with a million questions in between!) as it was common for them to have only seen snippets of the artwork on their way from the entrance to their room. I hope to think they grew lost in the story as do I, each time it’s told.

"When the staff at the Paediatric Ward approached me to create a second phase, the first thing I asked was, " can I draw with the children this time?!" And so began an engagement process and the beginning of stories inspired from their environment woven into the already established ones." - Rachel Viski

Date

September 29, 2017